I loved every story in Mimi Lipson‘s collection The Cloud of Unknowing —  so much that I couldn’t resist reading one, “Mothra,” out loud in its entirety. When I finished, my companion looked at me expectantly, then said, “Oh no. That’s the end?” I nodded. They laughed with appalled delight.

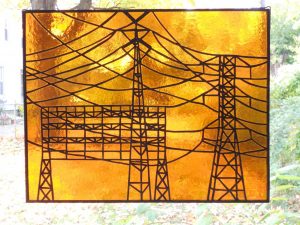

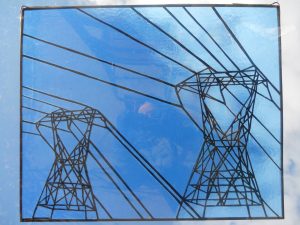

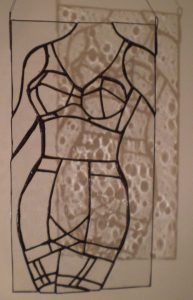

Mimi is also a stained glass artist; I’ve punctuated this interview with images of some of her pieces.

SR: Jenny Offill says and I agree that there’s a generosity to this collection, and I see it particularly in the way you shift points of view both between and within the stories; for instance, the reader seeing Isaac through Kitty’s eyes and vice versa. How do you decide which POV to use in a scene?

Thank you (and thank Jenny) for saying that. I guess generosity isn’t something every writer goes for, nor should they, but I do—as long as it doesn’t shade into mawkishness.

Anyhow, those switches in POV are usually a matter of instinct. Just, I get itchy with Kitty’s view, and bam, I’m in Isaac’s head. In retrospect I can see that the shifts are usually technical moves. They push a story along or to give it more dimension. It’s supposed to be good if the reader knows something about the narrator that the narrator doesn’t know about him-or-herself, and POV switches are a way of accomplishing this. It’s easy to communicate something about Isaac through Kitty’s eyes, and vice versa, without requiring either of them to have too much self-awareness. So maybe it’s another crutch.

Then sometimes a story will only work with a certain narrator. “Lou Schultz†is an example. It had to be told from Lou’s perspective because otherwise he would seem a little monstrous. Or anyhow he would just be a lousy parent, which in this day and age amounts to the same thing.

SR: One of the many things I really admire about this collection is that there are moments in each story that suggest the possibility of other, equally rich stories. In “Lou Schultz” when Lou remembers how he and Helena met, or in “The Endless Mountains” when the freight lines remind Jonathan of Lou’s anecdote about hopping a train and eventually presenting himself at the Enid, Oklahoma jail. Given all these possibilities, how do you decide how much narrative space to devote to each one? Would you want to write, for example, a longer Lou-and-Helena-in-their-youth story, or a story about Lou’s train-hopping?

ML: This is actually a big problem for me. The story-before-the-story is such a tempting device for enlarging a current world or a current relationship. I would maybe even call it a crutch—like writing about dreams or photographs. As you point out, it seems to happen more around the Schultz family. I don’t think anyone will be shocked to learn that most of the pieces in this collection take events from my own life as their jumping-off points, and so much of what I know or think about my own family is based on stories I was told.

To answer your question, though: Would I want to write those other stories? Yes. I guess everyone is interested in their parents as characters who existed in the world before they were born. But haven’t I already been self-indulgent enough?

SR: Does your background in linguistics influence your writing, and if so, how?

ML: I’m not sure about influence. I do think my interests in linguistics and in writing have a common source, which is (to use a mortifying expression) a love of language. I’ve always paid a lot of attention to the way people talk: how they can be characterized by their speech, and how they do things with language—for instance, using formality to dominate and informality to disarm. Or how grandiloquence can be comic. It’s Bugs Bunny stuff, really.

As far as linguistics goes, my initial attraction was to macro-level language structures—what’s called discourse analysis. That quickly led to sociolinguistics, which is more about the invisible rules and patterns of language change and variation. That, in turn, led me to formal linguistics. Eventually, we’re not even dealing with words anymore—just symbols and functions and stuff. So as things become more abstract and formal and technical, the two things—writing and linguistics—get further apart. I’d be hard pressed to find a connection between my writing and, say, the semantics of verb aspect.

Anyhow, I didn’t start writing seriously until I’d been out of the linguistics game for a while, but when I did, there was that mix of high and low—that functional use of register that made language structure interesting to me in the very beginning.

SR: Your characters Helena and Kitty seem to have some similar impulses to rescue, protect, and otherwise nurture difficult people, and also a similar capacity to see those difficult people’s positive qualities. Where do you think the line is between having strong empathy and making excuses for poor behavior?

ML: I guess you could say that the apple didn’t fall far from the tree with those two. As for me, I don’t know where that line is, but then I think a lot of people don’t. I don’t even know where the line is between a negative trait and a positive one. I often have misunderstandings as a result of talking about people or places in terms that sound disapproving when I don’t necessarily mean something bad—like how Kitty calls Los Angeles ‘apocalyptic’ in “The Searchlite.â€

SR:Â And of course the usual question: what are you working on now?

ML: Let’s just say I am working on a nonfiction project.