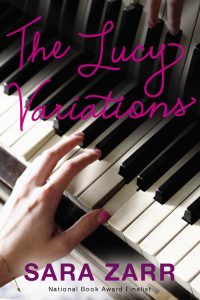

The Lucy Variations is about Lucy Beck-Moreau. As the book opens, Lucy is a sixteen-year-old former world-class pianist, and current…well, that’s the question. When your identity has been entirely constructed around one thing for as long as you can remember, and you walk away from that thing, how do you figure out what else there is, who else you can be? I loved this book, and I was excited to ask Sara Z. some questions about it. Minor spoilers below.

SR:Â Early on Lucy’s mom says that Temnikova’s death is ‘terrible timing’ — a cringe-worthy comment, but somewhat more understandable when you know that she was preparing Gus for an important performance. What was it like to write Lucy’s mom and Grandpa Beck, characters so focused on achievement that they often don’t seem to see other ways to experience life as even possible, let alone desirable? Was it easy, like letting a competitive part of yourself off the leash, or more of a stretch?

SZ:Â I was surprised how much I enjoyed writing Mom and Grandpa Beck – maybe you’ve tapped into something here about why I liked it. Maybe they represent my superego! As far as “easy” vs. “a stretch”, I think writing characters like that is always easy in the first draft, when they’re being the cardboard-cutout versions of themselves so that you can move conflict forward. In revision, for them to really work, they need to be humanized in some way. They need dimension, and opportunities to show cracks in the armor. That’s a writing challenge–you don’t want to pull your punches and make every antagonist into “a crank with a heart of gold,” because some people are just truly difficult or calcified. But, it’s very rewarding work. I love to see a previously-2D baddie or antagonist have a moment where they show another side or potential side, without quite joining the ranks of the “good guys.” One of my favorite and unexpected things about the final version of the book is the understanding Lucy comes to about her grandfather.

SR:Â I played violin growing up, and while I was never remotely close to the Lucy level, I definitely remember the stress of preparing for recitals, solo-ensemble festivals, & concerts. Do you play any instruments? How did you research the musical details in the book?

I grew up around music and especially classical music. My parents met in music school at Indiana University and were both quite good. My father, especially, had made it his career for a time earlier in their marriage. He conducted and sang, and held several professorships at music schools post-college. My mother plays guitar, piano, and cello, and is also a singer, songwriter, and arranger. By the time my sister were old enough to know what was going on, neither of my parents were making their livings in music but it was always a big part of our lives. I played the clarinet, and I was nowhere near Lucy’s level, either. My sister played violin and got to the point of playing in some competitions, and she could have probably gone further if that was her passion. As far as research, I did ask my mom some stuff, and I also attended a big piano competition that’s held here in Salt Lake (a fictional version of it appears in the book). I went to watch a master class, where a young musician performs a piece and then a seasoned and often well-known (in that world) musician critiques it and leads the musician through workshopping the piece. In front of an audience! I can’t imagine. The pressure seems incredible. A lot of Lucy’s personal interaction with the music just comes straight from my own love of those pieces.

SR: When did you decide to include the musical notations as section headings? I love them.

Thank you! This is one of those funny stories. I was talking to a colleague, E. Lockhart, on the phone about the book while I was still drafting it. And I don’t remember exactly, but I was kind of feeling uncertain and unfocused about how to present or organize it. And she said something like, “Well, it’s called The Lucy Variations so I assume you have it structured like a musical piece…” “Um, no. But that’s a good idea!” It was one of those things that seems so obvious now but hadn’t crossed my mind. Once I started thinking about it that way, it helped with the structure of the story. I’m always in favor of things that help with structure, because writing a novel is a fairly overwhelming task, as you well know!

SR:Â Early on, Lucy thinks: “She had to be careful with guilt. Once she went off that edge, the downward slide might never stop.” Perhaps it’s TMI to say it, but this passage really resonates with me. Why do you think guilt can be so seductive?

SZ:Â I wish I understood it better myself, as it’s one of my own personal trapdoors. I guess like a lot of things, guilt provides a kind of narrative for the events of your life story. It’s something to identify with, and in a way if you’re preoccupied with guilt maybe you feel like you have some control over the situation. “This thing happened and it’s my fault” (directly or indirectly, falsely or rightly) implies a kind of power, and maybe if it’s “about you” that way, it means there’s some hope for effecting a solution. Of course usually the things we feel guilty about aren’t in fact about us, and the solution isn’t up to us (at least not totally), and helplessness or powerlessness can be harder to face. Maybe! I don’t know.

SR: I love that Lucy decides to impress Mr. Charles by writing a paper about an author she knows he loves. I once tried very hard to love Crash by J.G. Ballard because of a particular instructor’s fondness for the book. What’s something you’ve done to impress a mentor?

SZ:Â In the first intensive writing workshop I ever took, I got a big crush on the teacher. He cited Ford Madox Ford’s THE GOOD SOLDIER as one of his favorite novels. So of course when I got home I read it, hated it and didn’t understand it, and emailed him to say how much I’d enjoyed it. I hope he doesn’t read this. (Hi Robert!)

SR: On a related note, another thing I think is great in Lucy Variations is that you show not just how appealing and thrilling it can be to have a mentor, but also the attractions and dangers inherent in being one. What makes mentoring relationships compelling to you to explore?

SZ:Â Oh, there are so many reasons! For one thing, it’s incredibly flattering when someone wants to do what you do and sees you as someone who has “arrived” in some way, especially in a professions in which there are so few tangible (or tangibly believable) evidences that you have something to offer, that your work matters in a lasting sense. Giving advice and encouragement is so much easier and enjoyable than needing advice and encouragement. Feeling established enough to warrant mentees is much better for the ego than feeling like a nobody. Being admired feels great. Those are the ego-based reasons, I guess. In a purer way, it’s so exciting to see talent in someone–especially someone young, or younger than you–and be in a position to help nurture it and encourage it. When you can successfully do that, you really feel like you’re doing something good for another person, directly, and it’s a moving thing. Then when it’s time to let go, and see your birdie fly the nest, that stirs up a whole lot of your own issues. As far as Will’s relationship with Lucy, I think there’s that pure side to his intentions, but he’s also human and nearing middle age. At one point in the writing process and in the midst of my own midlife crisis feelings, I went to see a friend’s daughter in her school play. And the youth and exuberance and beauty of the high schoolers on stage just killed me that night for some reason, completely leveled me. That fed directly into the scene where Will tries to explain to Lucy how painful it is sometimes to be so close to that kind of youth and beauty and talent, with his own sense of the newness of life and the act of creation behind him. Mentoring someone young lets you experience that again, and for a minute you can forget that it’s their life, not yours.

SR: Thanks so much, SZ!Â

miriam

May 9, 2013 at 9:02 amI love your interviews. Just sayin.

Sara

May 9, 2013 at 1:55 pmThanks! I enjoy coming up with the questions.